(New York) – Donor countries, the United Nations, and international financial institutions should urgently address Afghanistan’s collapsed economy and broken banking system to prevent widespread famine, Human Rights Watch said today.

The UN World Food Program has issued multiple warnings of worsening food insecurity and the risk of large-scale deaths from hunger throughout Afghanistan in coming months. The media have reported that families lacking money and food are selling their possessions and seeking to flee the country overland. Impoverished Afghans facing malnutrition have described desperate attempts to buy or forage for food, and the deaths of people unable to leave.

“Afghanistan’s economy and social services are collapsing, with Afghans throughout the country already suffering acute malnutrition,” said John Sifton, Asia advocacy director at Human Rights Watch. “Humanitarian aid is critical, but given the crisis, governments, the UN, and international financial institutions need to urgently adjust existing restrictions and sanctions affecting the country’s economy and banking sector.”

Following the Taliban’s August 2021 takeover of Afghanistan, millions of dollars in lost income, spiking prices, a liquidity crisis, and shortages of cash have deprived much of the population of access to food, water, shelter, and health care, Human Rights Watch said.

A woman living in central Afghanistan told Human Rights Watch that few in her community had money or food: “The teachers haven’t been paid for the past three months.… People are really desperate. When you don’t have food on your plate, you cannot think of anything else. No one has money to buy fuel, to warm the house once it snows, or to buy food.”

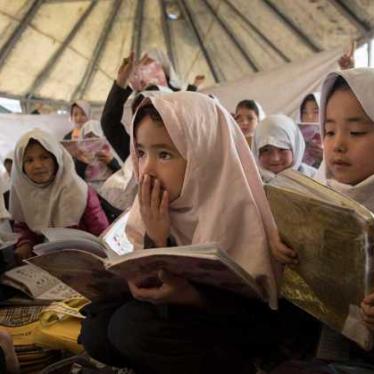

The financial crisis has especially affected women and girls, who face disproportionally greater obstacles to obtaining food, health care, and financial resources. The Taliban bans that are keeping women from most paid jobs have hit households in which women were the main earners the hardest. Even in areas in which women are still allowed to work – such as education and health care – they may be unable to comply with Taliban requirements for a male family member to escort women to and from work. The media have increasingly reported of families selling their children – almost always girls – ostensibly for marriage, to obtain food or repay debts.

Afghanistan’s dire economic situation has been exacerbated by decisions by governments and international banking institutions not to deal directly with the Central Bank of Afghanistan because of UN and bilateral sanctions by the US and other countries. This has increased liquidity problems for all banks and shortages of currency in US dollars and Afghanistan’s currency, afghanis.

Numerous banking officials and humanitarian agency staffers told Human Rights Watch that most Afghan banks cannot cover withdrawals by private actors and aid organizations. Even when funds are transmitted electronically into banks, the lack of cash means that money is not physically available and therefore cannot flow into the country’s economy.

US sanctions policy on the Taliban appears to be out of compliance with new policies that the US Treasury Department promulgated on October 18, Human Rights Watch said. The new policies state that the department “should seek to tailor sanctions in order to mitigate unintended economic and political impacts” while adopting a “structured policy framework that links sanctions to a clear policy objective.” Current US policies are not mitigating unintended impacts, nor are they manifesting a clear policy objective.

To address Afghanistan’s humanitarian crisis, Human Rights Watch recommends that:

- Governments, the UN, the World Bank, and the Taliban should work to reach an agreement to allow the Afghan Central Bank access to the international banking system. As an initial step, the US Treasury Department and other financial authorities should issue licenses and guidance to allow the Central Bank to engage in limited settlement transactions with outside private banks so that the bank can pay its World Bank dues and process or settle incoming dollar deposits from legitimate private depositors, such as UNICEF, the UN Development Program, remittance banks, and other legitimate actors.

- If an agreement involving the Central Bank is not possible, governments, the UN, and the World Bank should negotiate a short-term agreement with the Taliban to designate a private bank or other entity, independent of the Central Bank, to process large-scale humanitarian transactions to be monitored by officials with the World Bank, UN, or a designated third-party auditing entity. The US Treasury and other authorities should then issue guidance to allow the designated private bank or entity to utilize incoming electronic dollar deposits from humanitarian agencies to purchase paper US dollars outside the country and transport them, under international monitoring, for deposit in private banks in Kabul. Remittance banks should be provided with similar licenses to allow arrangements with private banks to facilitate legitimate US dollar transactions and, if necessary, physical shipments, monitored by an independent auditor.

- In the absence of any agreements, the UN should continue to use whatever means are at its disposal to continue shipments of money to Afghanistan for humanitarian purposes. The Taliban should cooperate in allowing these shipments, allowing deposits into independent private banks, and permitting the UN to utilize the funds independently and without interference.

- The US, along with other governments, should immediately undertake sanctions policy reviews, adjust current measures accordingly, and issue new licenses and guidance to facilitate liquidity and availability of cash to address the humanitarian crisis.

- UN Security Council members should take immediate steps to ensure that legitimate financial transactions related to humanitarian activities and the provision of other essential goods and services are excluded from the scope of UN sanctions.

- UN Security Council members should also reach agreement on issuing new guidance or “Implementation Assistance Notices,” and take other steps to ensure that UN sanctions do not present obstacles to legitimate financial transactions related to humanitarian and other essential work by international and Afghan actors.

“Donor generosity and humanitarian pledges can’t overcome the stark reality that UN agencies, humanitarian groups, and the Afghan diaspora cannot send assets to a banking system that isn’t functioning, and account holders in Afghanistan can’t withdraw cash that isn’t there,” Sifton said. “Widespread death and suffering from hunger are preventable if governments act urgently to address Afghanistan’s economic crisis.”

For additional information about the financial situation and Afghan accounts about the situation, please see below.

Afghan Accounts of the Humanitarian Crisis

Afghans in several provinces said that wages have nearly disappeared in most sectors, especially in urban areas, and that food prices are rapidly increasing. Some gave accounts of families selling their property or their children to pay traffickers so that they could flee the country.

“Farid,” a pseudonym, said he recently fled to Iran, but Iranian authorities detained and then deported him. He described seeing hundreds of families, many with small children, trying to leave the country with insufficient money, food, and clothing. He said that he now has no means to support his family or purchase food:

“We don’t have enough food … we only eat once a day. With the winter approaching, the situation can get even worse than this. The Afghan [Taliban] government doesn’t have any clear plan to fix the hunger issue, and I doubt if the international community has one. What I clearly see is that soon most Afghans will die just for not having food, and as always, no one will care.”

He said that traffickers are taking advantage of the situation by charging US$500 to $700 to smuggle people to Iran. “I also saw the bodies of people who have died in the deserts leading to the border,” he said. “I had to sell all I had to pay the traffickers.”

“Sharzad,” a woman in southeast Afghanistan, said the humanitarian situation is “worse than what appears in the media.” She said: “The shops are closed; girls don’t go to school. The banks pay only a fixed amount, and you must wait in long queues to get that … The situation is very bad. People are very poor.”

She said she had seen “terrible scenes” at the bazaar: “[S]mall kids were begging every customer in front of the bakeries to buy them a loaf of bread, and no one could afford to pay for even one more loaf of bread for those kids.”

She said that prices were increasing every day and that she expected people to die this winter:

“The winter is very cold, and people cannot heat their houses. No one works, especially women, and even those who used to work have not been paid yet. One neighbor told me yesterday that she doesn’t have anything in the house to feed the kids. Every night, she puts on her burqa and takes all her seven kids with her, and they go door-to-door to see if anyone will share their dinner with them. They only eat once a day if anybody gives them some food. One family offered to buy her one-year-old daughter for US$600, but she refused the request, as she wanted to keep her daughter.”

“This is the worst nightmare anyone in the world has ever imagined,” she said.

“Sitara” described people foraging in already-harvested agricultural fields:

“One of the worst cases that I have witnessed in my life was seeing an old man with kids searching the potato fields hoping to find some remaining potatoes, to be able to feed themselves that night, although the crops had been harvested two months ago. If the Taliban and the international community don’t pay attention and do not help people, everybody will die.”

Factors Affecting Afghanistan’s Economic Crisis

Multiple factors are causing or exacerbating Afghanistan’s current crisis, including cutoffs in foreign assistance that paid salaries of millions of public and private employees, mass withdrawals from private banks, and a collapsing economy. These factors include the Taliban’s past links to Al-Qaeda, disastrous prior period of governance, failure to keep public commitments, and horrific human rights record – in particular, with respect to women and girls and religious minorities. These factors have helped make governments and international financial institutions unwilling to recognize the Taliban government or allow institutions that the Taliban now control to operate as governmental entities within the international financial system.

The US Treasury has reaffirmed that existing US sanctions on the Taliban and certain Taliban leaders – imposed in connection with earlier UN Security Council resolutions addressing the group’s links to terrorism – still apply. UN agencies and member states remain bound by UN Security Council sanctions.

The United States, a key actor in the international financial system, has blocked Afghanistan’s Central Bank from obtaining credentials needed to engage in transactions using the US and international banking systems. The US Treasury has prevented the bank from accessing foreign currency reserves, even as collateral to provide short-term liquidity to settle dollar transactions or to pay dues to the World Bank. At the World Bank, the US government has led a process to prevent the Central Bank from accessing World Bank assets, grants, or assistance, which, in any case, it would be unable to transfer because of the bank’s lack of access to the international banking system.

Absent new actions or guidance from the Security Council’s relevant sanctions committees, which would require the agreement of all other council members, it remains unclear if UN sanctions apply to the Central Bank or to transactions involving government offices or ministries controlled by sanctioned people. Some UN agencies and implementing partners remain uncertain about what transactions they may undertake with government entities. Recent US Treasury licenses and guidance allowing transactions involving humanitarian activities do not address many other legitimate transactions, or the status of the Central Bank or its credentials, and have not addressed underlying liquidity or cash shortage issues.

Afghanistan’s Central Bank has imposed limits on withdrawals of local currency by account holders and private actors and prohibited many types of electronic transactions in US dollars. Private banks lack adequate local currency to cover withdrawals, have few or no dollars in cash, and do not appear to be providing credit. They are also facing difficulties settling incoming dollar transactions via correspondent accounts at private banks outside the country, most likely due to foreign banks’ fears that they may be violating sanctions.

The Central Bank’s inability to conduct transactions in US dollars or obtain US dollars in paper currency are major factors in Afghanistan’s economic crisis. Dollar transactions, both paper and electronic, are integral to Afghanistan’s economy. Most of the country’s gross domestic product in the last three decades have initially entered the economy in dollars – such as donor money, remittances, and export income.

At the same time, shortages of local currency also remain acute and can be expected to worsen over time with inflation, physical decay of banknotes, increasing personal debt, and growing economic inequalities. Companies that print Afghan currency in Europe, understandably concerned about the Central Bank’s credentials and sanctions issues, cannot ship new bills to Kabul. Taliban authorities have no capacity to print money.

Even where legitimate electronic transactions are possible, Afghan banks and foreign financial institutions with local agents in Afghanistan, including vital remittance services and banks, do not possess enough afghanis to cover withdrawals, are unable to provide dollars, and cannot obtain either currency from the Central Bank in substantial amounts. Numerous legitimate account holders are unable to access balances or money sent to them.